Tom Cruise's Scientology Gala Incident: A Breakdown of the Behavior and Reported Aftermath

Two celebrity-led events unfolded on opposite sides of the Atlantic recently. On the surface, they share little in common. In Los Angeles, the Baby2Baby Gala was a masterclass in polished public relations, a star-studded affair that culminated in a clean, triumphant, and easily digestible metric: $18 million raised for children in need. It’s the kind of number that headlines write themselves.

Meanwhile, in the quiet English town of East Grinstead, another high-profile event took place: Scientology’s annual Patrons Ball, headlined by its most famous adherent, Tom Cruise. This gathering produced a different set of data points, not of dollars raised, but of disturbances logged. We have reports of a low-flying helicopter, panicked animals, gridlocked roads, and a general sense of public chaos.

One event presents a pristine profit-and-loss statement, a clear charitable gain. The other presents a messy, unquantified list of negative externalities—costs imposed on a public that never bought a ticket. The contrast isn't just about good versus bad optics; it's a case study in two wildly different forms of accounting for celebrity impact. One is for public consumption, the other is a debt someone else is forced to pay.

The Sanctioned Ledger

Let's first examine the Baby2Baby model. The gala, held on November 8th, was an exercise in precision. The key figure, a record-breaking $18 million, is the entire story. It's a quantifiable success. The event's architecture is designed to produce this number. High-value assets (celebrities like Serena Williams, Lizzo, and Alicia Keys) are deployed to generate maximum return on investment, which in this case is charitable donations. The entire operation is transparent in its objective and its outcome.

Think of it like a blue-chip company's quarterly earnings report. The numbers are audited, the messaging is controlled, and the value proposition is clear. The public receives a simple, positive narrative: famous people leveraged their influence for a measurable social good. There are no hidden costs, no collateral damage to residents, no reports of civic disruption. The event's "balance sheet" is clean.

This is the idealized transaction of modern celebrity philanthropy. Fame is converted into capital for a cause, and the process is frictionless for anyone outside the ballroom. I've looked at hundreds of these event prospectuses, and the successful ones all share this trait: they contain their impact, ensuring the only thing that escapes the venue is a positive press release. It's a closed system designed for efficiency. But what happens when the system isn't closed?

The Unaccounted Externality

Now, consider the East Grinstead incident. The data here is qualitative, anecdotal, and overwhelmingly negative. Residents described Tom Cruise’s helicopter arrival as a "right old racket" that was "scaring the animals." One report detailed How Tom Cruise’s Risky Behavior at a Scientology Gala Left People & Animals Terrified. The event drew thousands of attendees—over 7,000, to be more exact—to a community not built to handle the logistical strain. Roads were shut down, traffic was gridlocked, and a minibus was even involved in a collision.

These are what economists call negative externalities: costs incurred by a third party that isn't involved in the transaction. The transaction was the Scientology gala; the third party was the entire town of East Grinstead. Unlike Baby2Baby's $18 million, you can't easily assign a dollar value to a terrified dog or an hour spent stuck in traffic. So, it simply goes unrecorded on the official ledger.

The Church of Scientology's spokesperson offered a boilerplate defense, stating the event featured "community festivities" and that all planning rules for the massive marquee (reportedly 45,000 square feet) were followed. This is a classic corporate non-denial. It addresses procedural compliance while completely ignoring the substantive impact. Following the rules for building a marquee doesn't negate the chaos caused by your logistics.

This is the part of the analysis that I find genuinely puzzling. The calculation seems so shortsighted. The cost of, say, arranging a shuttle service from a remote parking area is a quantifiable expense. The reputational cost of being seen as a menace to an entire town is far higher, yet it's treated as an acceptable rounding error. It’s like a factory saving money by dumping pollutants into a river; the profits are booked internally, while the public downstream bears the real cost. The gala’s private benefit was financed by a very public nuisance.

A Flaw in the Ledger

The core discrepancy isn't about charity versus religion, or Serena Williams versus Tom Cruise. It's about which costs we're shown and which are deliberately kept off the books. The Baby2Baby Gala is a sanitized, investor-relations version of a celebrity event. Its success is measured by a single, positive number that is broadcast to the world. The Scientology gala reveals the hidden operating costs—the disruptions and public frustrations that are never included in the official accounting. One tells a story of value creation; the other, of value transfer, where convenience for the few is subsidized by the tolerance of the many. The real metric of an event’s success shouldn’t just be what happens inside the tent, but also the noise it makes for everyone outside of it.

Related Articles

Immaculata's Open House: A Data-Driven Breakdown for Prospective Students

On the surface, the announcement is unremarkable. Immaculata University, a private institution nestl...

Brad Gerstner's Vision for the Next AI Titan: Why AMD's 'Bet the Farm' Move Could Change Everything

Every so often, a piece of news hits my desk that feels less like an update and more like a tectonic...

Fifth Third Swallows Comerica for $10.9B: Why It's Happening and Why You Should Care

So, another Monday, another multi-billion dollar deal that promises to "create value" and "drive syn...

Tesla's Troubles: Elon's Distractions vs. Sales Data

Elon's UK Meltdown: Can Tesla Survive Musk's Political Circus? Tesla's facing a serious problem in t...

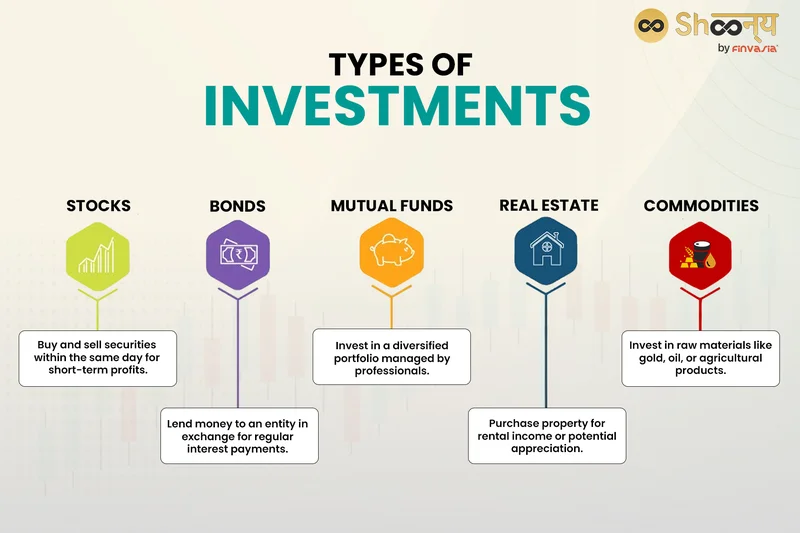

Analyzing 2025's Investment Landscape: What the Data Reveals About Top Asset Classes vs. Low-Risk Alternatives

There's a quiet, pervasive myth circulating among the baby boomer generation as they navigate retire...

Dan Schulman Named New Verizon CEO: What His PayPal Past Means for Verizon's Future

Verizon’s New CEO Isn’t About 5G. It’s About a Quiet Panic. The market’s reaction to the news was, i...